Photo of My African House

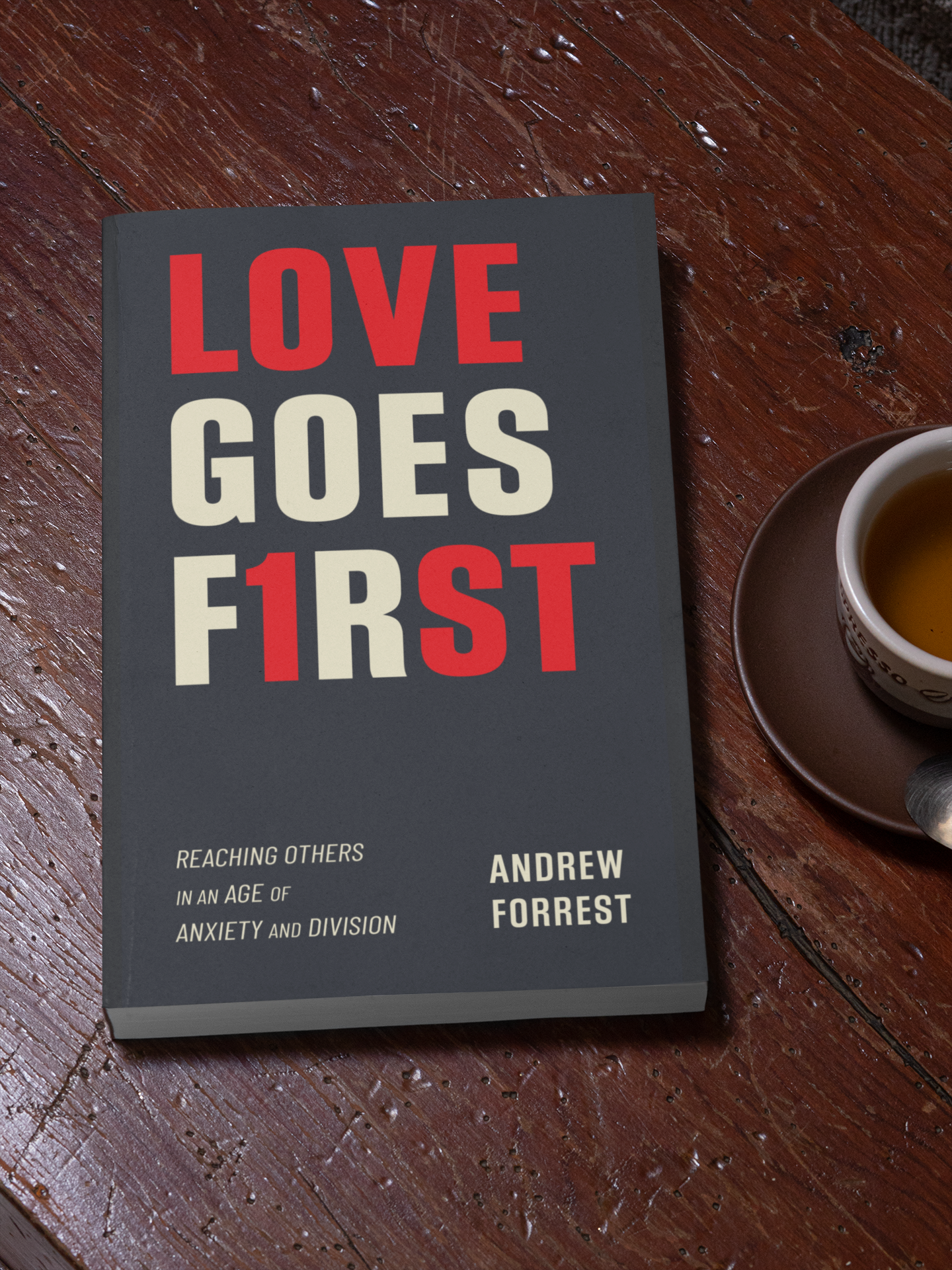

I have a new book coming out in October. It’s called Love Goes First: Reaching Others in an Age of Anxiety and Division.

In a world of division and polarization, how we do actually reach the people on the other side? That’s what my new book is about.

My mom recently digitized some old photos, and she shared a couple of them on our family text thread. The photos made me think of a little story I tell in the book, which I share below, and I thought the photos might help you get a sense of the story.

In the photo at the top of the post, you can see the house we lived in, perched as it was on the side of a small mountain in Freetown, Sierra Leone, West Africa. From our house, you could see all the way to the harbor (Freetown has a natural deep water harbor) and the ocean.

Sierra Leonean women carry their burdens on their heads. In the second photo above, you can see the women carrying bundles of firewood, with which they will make charcoal. I’m pretty sure that leafy tree on the left of the photo is a mango tree, though it’s hard to tell.

The reason I point out the mango tree is because of an anecdote I relate in my upcoming book (pre-order!) about something my mom would say to us when we wanted play in a nearby mango tree. I share the excerpt below.

“They’re More Scared of You Than You Are of Them”

When I was a little boy, I lived with my family on the side of a small green mountain in West Africa. Our house on the verdant mountainside was surrounded by mango trees. Mangoes are good for eating and mango trees are good for climbing, and the best mango tree for climbing was the big one at our neighbor’s house. Our neighbor lived across a small, shallow valley from our house, and there were two ways to get there: the long way and the short way. The long way was the road, which curved around the side of the valley in a broad loop. Since boys don’t like taking the long way, we never took the road. It was far better and faster to cut across the valley, following a small dirt footpath that ran directly to our neighbor’s house. This path cut through a shallow bowl of tall reeds and grasses, reeds so tall that once you entered the path, you could see neither right nor left. At times, as my brother and I ran along the path, we’d spot a black form with a red belly rustling and slithering across the path in front of us: a spitting cobra. My love for climbing the good climbing tree at my neighbor’s house made me want to cross the valley, but I always did so with a fear of meeting a cobra. I would run along the path so fast it felt as if my feet barely touched the ground.

Our green little mountain was infested with spitting cobras, which are exactly what they sound like: cobras that rear up and spit venom at the eyes of their prey. Once, my nearsighted dad came around the corner of our house and startled one of these snakes, which swayed up and spit venom at him. Fortunately, my nearsighted dad wears glasses, and when he came sprinting back inside the house, we could see the milky venom dripping off his lenses. I’ve never liked cobras.

My brother and I would whine about the snakes living around us, but my mom adopted her Pollyanna persona and wouldn’t accept our complaints. She would tell us, “Boys, they are more scared of you than you are of them.” I think she got her herpetological information from that scene in The Parent Trap where the gold-digging fiancée is set up by the twins and convinced to tap sticks together to scare off California bears. My mom’s advice was essentially to make lots of noise whenever we ran around outside, certain that our noisemaking would scare away any lurking cobras. Sometimes, as we ran across the valley to that wonderful mango tree for climbing, we’d clap our hands and yell like little idiots, hoping that our mom was right and all the cobras were fleeing before us.

But if I’m honest, even as a small boy I had my doubts about the truth of her claim about the psychological state of our neighborhood cobras— “Boys, they’re more scared of you than you are of them”— primarily because it didn’t seem possible for a venomous, coldhearted reptile to experience terror greater than the kind I felt as an imaginative little boy. Even to this day I do not care for snakes and find it entirely appropriate that the Bible tells us it was a serpent that brought evil into Eden. But now, as an adult, I have decided that my mother was more right than she realized. She may not have known anything about snakes, but her insight is accurate when applied to other people: They tend to be more scared of you than you are of them.

Now, of course, it is not actually true that everyone nearby is walking around in fear of your presence—to say that other people are “more scared of you than you are of them” is a bit tongue-in-cheek. What I mean when I use that phrase is that people are naturally reactive; we observe what others do and how others act before we decide how we will act. To act first, therefore, without regard to how someone else is acting is a radical departure from the natural human tendency. So though other people are probably not shaking in their boots when they see you coming, they are nevertheless naturally inclined to base their actions off whatever you do….

[end of excerpt]

I’m excited about this upcoming book, and I want to get the message out. If you’d pre-order a copy at your preferred bookseller, it would really help, because pre-orders communicate to the booksellers that this is a book they should get behind and really market.

July 4, 1826

I have a new book coming out in October. It’s called Love Goes First: Reaching Others in an Age of Anxiety and Division. The book is about how we can actually move forward and reach the people who disagree with us, even the people who hate us.

(Please pre-order! Here’s the Amazon pre-order page, though you can pre-order at any bookseller you prefer. Every single pre-order sale will help get the message of the book out, because pre-order sales tell booksellers if a book is worth pushing and investing in.)

One of the things I do in the book is include lots of examples that illustrate what it means to go first, including one about July 4, 1826. So, here on the Fourth of July, allow me to share with you a few pages from my book.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both died on the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1826. Jefferson died at Monticello, his Virginia home, at around one o’clock in the afternoon. He was eighty-three years old. That same afternoon, Adams lay on his own deathbed, surrounded by loved ones: “Adams lay peacefully, his mind clear, by all signs. Then late in the afternoon, according to several who were present in the room, he stirred and whispered clearly enough to be understood, ‘Thomas Jefferson survives.’”

Then a few hours later, at about six-twenty in the evening, John Adams died. He was ninety years old. Both men had lived to see the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and each man died believing the other still survived. The fact that they both died on the same day is amazing. The fact that they died as friends is a miracle.

Both Adams and Jefferson were relatively young men when they were tasked by the Continental Congress with the writing of the document that would enumerate the reasons the thirteen colonies were declaring their independence from King George—when the Declaration of Independence was signed on July 4, 1776, Adams was forty and Jefferson only thirty-three. Although their signatures on the document prove that they were united in spirit and purpose at that point in their lives, as their long and distinguished careers played out, they became bitter enemies and had no contact with each other for years. Both served as president of the United States, but in rival parties, with Jefferson succeeding Adams to the office—two of the great men of the American Revolution implacably estranged from each other.

Their mutual friend—and signer of the Declaration from Pennsylvania—Dr. Benjamin Rush was grieved at the enmity between Adams and Jefferson and tried for several years to get them to reconcile. Then, in December 1811,

just before Christmas, Adams heard again from Benjamin Rush who wished to remind him of a visit Adams had had the summer before from two young men from Virginia. They were brothers named Coles, Albemarle County neighbors of Jefferson’s, and in the course of conversation Adams had at length exclaimed, “I have always loved Jefferson and I still love him.” This had been carried back to Monticello, and was all Jefferson needed to hear. To Rush he wrote, “I only needed this knowledge to revive toward him all the affections of the most cordial moments of our lives.” “And now, my dear friend,” declared Rush to Adams, “permit me again to suggest to you to receive the olive branch offered to you by the hand of a man who still loves you.”

On New Year’s Day 1812, seated at his desk in the second- floor library, Adams took up his pen to write a short letter to Jefferson. . . .

The brief letter from Adams immediately produced a response in Jefferson:

If, as stage-managed by Rush, it had been left to Adams to make the first move, Jefferson more than fulfilled his part. “A letter from you calls up recollections very dear to my mind,” he continued. “It carried me back to the times when, beset with difficulties and dangers, we were fellow laborers in the same cause, struggling for what is most valuable to man, his right of self-government.”

In the fourteen years that followed their dramatic reconciliation, both men exchanged dozens and dozens of letters on every possible topic. Though they were both old men in those years, they recalled and relived the months and moments of that bright time in their lives, decades before, when they were part of the great events of the American Revolution. Their letters are a precious gift to posterity and part of the inheritance of all subsequent Americans.

They are also a testament to the life-changing power of forgiveness and the catalyzing potential of going first. What if, resisting Dr. Rush’s prodding, Adams had refused to send his initial letter to Jefferson? What if Jefferson, nursing decades-old grievances, had refused to reply? I find it fascinating—though not at all surprising—that these great men of American history just needed someone to go first to turn them back toward each other and move them toward reconciliation. They each wanted to be liked by the other. For Jefferson, what moved him was the repetition in his presence of a chance favorable remark Adams had uttered to someone else; for Adams, it was the knowledge that Jefferson still loved him and had said so in a letter to Rush. The whole story is beautiful—a little jewel of American history.

Happy Fourth, everyone.

Note: the block quotations above are from David McCullough’s biography of John Adams.